Ryan Griffith | Indianapolis Theological Seminary

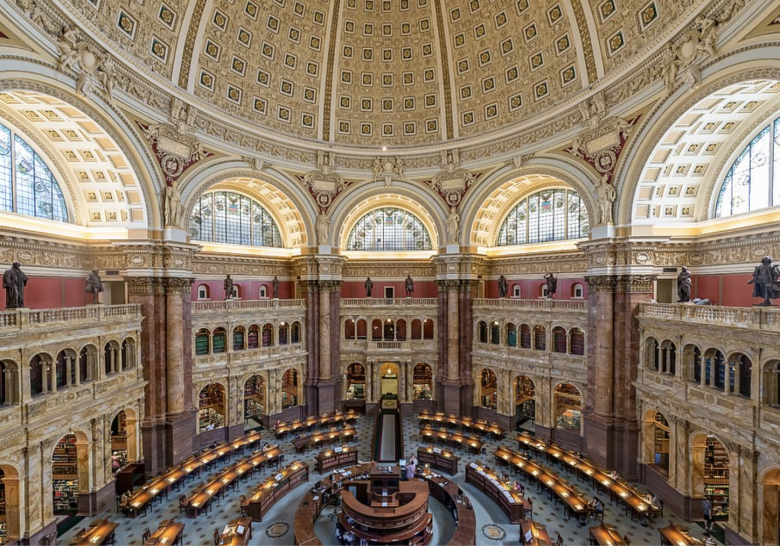

Although library archives are most often the domain of historians and other students of the humanities, research interests will take seminary faculty into the archives from time to time. Even biblical scholarship can unexpectedly require archival research—whether to investigate a rare manuscript or to access a theologian’s unpublished correspondence. Whatever the occasion, digging around in university archives can be an inspiring experience. If you don’t plan well, however, it will be inefficient and frustrating—particularly if you are traveling to a university far away from home.

A measure of advance planning will make a research trip more enjoyable and productive—and potentially save you or your students from having to make a costly trip to a distant archive more than once. Unfortunately, graduate-level research courses sometimes neglect practical guidance on archival research. If you teach and supervise graduate (especially doctoral) students, consider including a guide to archival research as part of your regular instruction.1

Here are some tips for getting the most out of a research trip.

Plan Well in Advance

Long before you visit, you should know where materials are, when libraries and archives are open, and what permissions you will need in order to access them.2 Library archives require significant advance notice—usually no less than two weeks—if you are planning to visit. In many cases, you will need to submit several forms of identification and letters of reference from your university or department head before you can set up a research appointment.

Check with each archive you intend to visit to make sure you fully understand its policies. While you might be able to request items on site when you are working at a small library with a dedicated archivist, most archives require you to order the documents you desire to view well in advance. If you don’t, you may wait for hours while they are retrieved—if it is even possible for them to be retrieved the same day. At large universities, items you are interested in may be in different collections or even in different libraries (which, occasionally, may be in different parts of the city). Use the archive’s online catalogs and finding guides and ensure that your document requests are accurate and submitted weeks before your visit.

Manage Your Time With Care

Recognize that work days are often shorter at European universities—and some archives will close for “tea” at noon. One archive I’ve occasionally visited doesn’t open until 9 a.m., takes an hour break over lunch, and closes for the day at 4 p.m. That translates into precious little research time, so it is critical to know what you’re looking for.

Arrange your requests by priority, so you have the most time with the items you know to be of greatest importance. You don’t want to be finally looking at an essential document as the archive closes for the day. When planning the length of your visit, consider the amount of material you intend to see.

Take Pictures of Everything

I have frequently worked with archival documents that were not yet listed in any digital catalog (cardcatalogs and, occasionally, handwritten finding guides). Recording how you found each item is essential for giving accurate attribution in your writing. I even take pictures of folders and card catalog entries so I have a solid trail.

You can also make better use of your time by photographing—rather than reading in detail—the material you access. I use an iPhone for a few reasons: First, the iPhone’s camera takes quality photographs, geotags them, and provides some basic organization. Second, if I’m on Wi-Fi at the library, the iPhone automatically backs up the photos to a cloud storage service. Finally, using the iPhone means I don’t have to lug around a camera or keep up with SD cards.

For any document you don’t photograph on site, you will have to pay a researcher to retrieve and scan if you later discover you need it. Also keep in mind that archives will sometimes charge you a fee to photograph documents, even if you are doing the photographing. Many libraries will waive these fees for PhD students, but be sure to find out in advance.

Build Relationships

As every researcher learns, the most important resource in the library is the librarian. Communicating in advance with intentionality and kindness can go a long way toward making your research successful. A paper (or email) trail of your communication history may also be necessary if the archivist is suddenly unavailable when you arrive. Author Tom Reiss once traveled to an archive with which he had briefly lapsed in communication, only to find that the archivist had died shortly before his arrival.

In addition to arranging permissions and details for your visit, be sure to tell the librarian (briefly) about your research interest; he or she may direct you to materials you had not discovered. If there is tea, take the opportunity to enjoy it with the library staff or faculty. I got to know several university researchers this way—including one who has become a good friend and fellow collaborator on a future project.

Be Grateful

In addition to verbally (and frequently) expressing your gratitude, take a gift for the archivist—a coffee cup, an item with your university’s logo, or something that is distinctive from your state or hometown. Archivists do difficult and oftentimes thankless work. When you get home, take time to write them again. Sometimes this simple act of gratitude and communication will encourage them to keep you in mind in the future. It has been two years since I visited a particular archive and I still get emails from its archivist when he unearths something new related to my work (he recently sent me more than two dozen scans).

Apply for Research Funding

Your university or department may have research funding or travel grants available. Be sure to speak with your supervisor and department head. You might also check guilds and societies that are associated with your discipline. For example, the Conference on Christianity and Literature offers grants to students as well as scholars and independent researchers.

Again, remember to plan ahead. If you are planning for summer research, remember that grant applications are typically due in the fall. Even a small grant goes a long way when you are a struggling junior faculty or a PhD student.3

This article was first published in print in Didaktikos: Journal of Theological Education. Sign up today for free.

- For one such resource, consider Samuel J. Redman, Historical Research in Archives: A Practical Guide (Washington, DC: American Historical Society, 2013).

- The Society of American Archivists maintains a list of archives as well as useful tips for evaluating and using them (“Finding and Evaluating Archives,” Society of American Archivists,” last modified 2 September 2011, www2.archivists.org/usingarchives/findingandevaluating).

- 3 See “Awards and Grants,” www.christianityandliterature.com/Awards-and-Grants. The Society of Biblical Literature, more familiar to biblical scholars, awards a number of grants each year (“SBL Awards,” www.sbl-site.org/membership/SBLAwards.aspx). The Forum for Theological Exploration also hosts more a comprehensive list of scholarships and grants (“Fund Finder,” https://fteleaders.org/fundfinder).