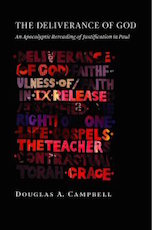

Recently, I sat down with Dr. Douglas Campbell, Professor of New Testament at Duke Divinity School and author of this month’s Plus One, The Deliverance of God: An Apocalyptic Rereading of Justification in Paul.

Recently, I sat down with Dr. Douglas Campbell, Professor of New Testament at Duke Divinity School and author of this month’s Plus One, The Deliverance of God: An Apocalyptic Rereading of Justification in Paul.

DM: What pushed you to write The Deliverance of God? What aspects of current scholarship were you wanting to address in this work?

DC: Well there were a couple of things going on. The thing that was really driving the book was the realization that there’s a fundamental difference between a covenant and a contract. So a covenant, understood in the most theologically constructive sense, is an unconditional relationship in which you covenant to someone – you commit to an unconditional covenant. You initiate a relationship and you stay in a relationship with that person, or that group of people. For good. Permanent. It’s irrevocable. And you have very strong expectations about how people should behave within the covenant. You don’t break it. That’s a fundamentally different account of relationships from a contract, where I enter into a relationship with you only on the proviso that you fulfill certain conditions. And if you don’t fulfill all those conditions, I break off the relationship with you.

Now, think about that. Our society structures most of its public relationships in terms of a contract. Political relationships, legal relationships are contractual. But our most important relationships are covenantal. Our family relationships are covenanted. I have a daughter and I have a son. And they’re not my daughter and my son because they fulfill certain requirements and we’ve entered into a contract of parenting and childhood so that if they fail to fulfill those requirements that relationship will be terminated. My relationships with my daughter and my son are irrevocable. They will always be my son and my daughter. No matter what they do and no matter what I do, I will always be their parent. They will always be my children. And that’s how God relates to us. It’s terribly important that our relationship with God is covenanted because that’s a relationship of love. A contractual relationship is not a relationship of love. It’s a relationship of justice. These two moral narratives are fundamentally incompatible as accounts of God.

I realized a lot of Pauline debates were caught up in this distinction without recognizing it. The old perspective is unfortunately basically a contractual account of how God relates to us. It’s a contractual account of how God relates to humanity, based on works. If you do these things, you’ll be saved, and if you can have faith, you’ll be saved.

In the parts of Paul that I really resonate with, like Romans 5:1-11, God loves us and commits to us in Christ before we do anything right. While we were still sinners, Christ died for us. That is the covenant. So I suddenly realized there was an interpretative collision going on, deep down in the way we were interpreting Paul, which was messing up everything else that we were doing. I had to address it. I had to find out, “Was Paul confused? Was he an old perspective guy deep down all the time? Was he a covenantal thinker all the time?” This is what we want. And the stakes are fairly high here.

And so the book came out of the realization that we can read Paul in a way that is consistently covenantal. We don’t have to pay this price. We don’t have to say that Paul is muddled up. We don’t have to say that Paul was ever committed to a contract. The enthusiasm of some interpreters for contractual salvation has led to them finding that in Paul, but it’s not really there. That’s what led to the book. But it’s quite a deep issue. It’s a big one, it’s broad, it’s complicated.

DM: Based on some push-back that I’ve read regarding your view as a whole, especially Tom Schreiner’s response to your chapter in Four Views on the Apostle Paul, his main critique was that you don’t have a role for judgment in your understanding of Pauline theology. Would you like to respond to that?

DC: Yeah, well he’s wrong. I’ve got plenty of room for judgment. There’s a lot of accountability in what I’m talking about. Everybody in Christ will rise and have to give an account of themselves to God. What’s missing from my account is Tom Schreiner’s version of judgment. I consider this to be a great advantage because I wouldn’t want Tom’s view of judgment to be in my account of the Gospel because I don’t think it’s compatible with the Gospel, because any notion of judgment has to be reconstructed by the Gospel.

I work a lot in justice and prison work, and one of the first things that you learn is that there are a lot of different definitions of justice out there. Some of them are harsh, some of them are nasty, and some of them are kind and constructive. What we need to do as Christians is let our understandings of restoration and accountability be reconstructed by Christ, and by Christology, and by the pressure of our Christian situation, and not bring in our cultural baggage.

I don’t see any indication that Tom’s account of final judgment has been reconstructed by Christology. All I see is a political and cultural override of what Christ is trying to say about justice and judgment. And I think this is a major problem. God is not characterized fundamentally by retribution. God is not characterized fundamentally by the need to punish. If he is, then the doctrine of the Trinity is ruptured, which I think would be a very bad idea. God is certainly characterized by justice conceived in terms of restoration, and covenantal accountability, and transformation, and resistance to evil, and these things are entirely legitimate. So we’re probably a little closer together at these points than he thinks.

DM: At Duke, not only are you training up the next generation of scholars and professors but you’re also training pastors as well. How do you want the next pastoral generation to take the essence of your understanding of Pauline theology and implement that into their congregations in their ministries?

DC: Well I do spend entire semesters on this – it’s huge. Let me just say a few things. I encourage people to really submit themselves and allow God to be in charge of the truth process. Trust God to reveal stuff to you, rest in God. Don’t try and work it out for yourself, don’t try and base it on your own understanding. Kind of, let go and let God, and rest in that. So I think that’s actually very important, because it stops people falling into a set of traps, where you might try and work it out yourself and then what you’re working out proves to be a foundation that collapses. It’s a house of sand. You’ve got to build your house on the rock— on God. And it’s believing that God actually does stuff in your life now, God’s alive, that’s very important. Which sounds kind of basic, but actually standing up in a classroom and saying repeatedly, “God is here now and works in your life and your relationships and the communities,” is actually shocking to some folks. But that’s what needs to be said.

Second, I think this will push you into very practical, very particular relationships. God is interested in friendships, what I call “strange friendships”. He’s interested in Christians that can be flexible enough and confident enough to reach out to people who don’t look like them and to create covenantal relationships with these people. This is how Paul operated. He made friends. He was an expert friend maker and he made friends with very odd people; with prisoners, with women, with hand-workers, with high-status people, with low-status people, with non-Jewish people, with Jewish people. He was always making friends and this is what made the whole thing work. So that’s another thing that I emphasize; friendship evangelism and network evangelism. I talk about that a lot. And going in with the right attitude and acting in the right way within those relationships.

I also emphasize the importance of prisons and the prison-industry. Paul wrote 40% of his letters from an incarceration. And it’s very difficult to understand what that means if you haven’t visited a place of incarceration. Maybe even spent a little bit of time there. Go and hang out with some prisoners as Paul certainly did. This was a very, very big part of his life. And it should be a very big part of the church’s life. So I’m theoretically, but also practically, very strongly committed to getting prison visitation programs going, restoration processes going, restorative justice processes going, re-entry programs going, etc. This is part of what Paul was about, and if you’re not doing it, you’re not getting it.

* * *

The Deliverance of God is available for only 99 cents during the month of February. You can also get a differing opinion with Justification Reconsidered by Stephen Westerholm, February’s Free Book of the Month.

The Deliverance of God is available for only 99 cents during the month of February. You can also get a differing opinion with Justification Reconsidered by Stephen Westerholm, February’s Free Book of the Month.

DAC’s DOG, which i consumed in excruciating detail over 3 years, is 1300 pages of very scholarly yet utterly and unequivocally pure heterodoxy. He jumps thru hoops and performs remarkable contorsions in an Herculean effort to strip any vestige of “Justification by Faith Alone” from Xity, and in the process to essentially tear the heart right out of the Reformation, which is not such a big deal today, as Protestantism is a mere shell of what Calvin and Luther intended. When DAC is done, all that’s left of the Gospel is a large dose of card-carrying works righteousness, pure and simple. That’s my 2 cents.