Photos by Tavis Bohlinger

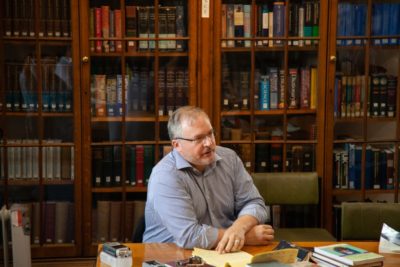

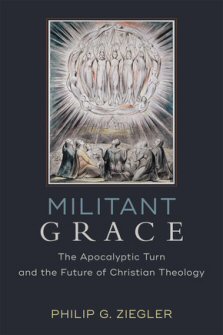

One of the advantages to living in the UK is the ease with which one can get from London to Manchester, Oxford to Edinburgh, or, in my case last week, from Durham to Aberdeen. I found out on very short notice that Philip Ziegler, personal chair in dogmatics at King’s College, University of Aberdeen, was holding a symposium in which other scholars at Aberdeen engaged critically, and constructively, with his recent book, Militant Grace: The Apocalyptic Turn and the Future of Christian Theology (Baker Academic, 2018).

I had actually just finished reading the book and thoroughly enjoyed it (Ziegler writes with striking prose), but I was left with some nagging questions. So I booked a last-minute ticket up to Aberdeen last Thursday and settled in for the 5-hour train ride, much of it along the stunningly rugged coast of Scotland. Good thing I have a Kindle.

At the symposium, papers were presented by Dr. Katherine Hockey, Kevin O’Farrell, and Jacob Rollison. Their individual critiques corresponded to the three major sections of the book: “The Shape and Sources of an Apocalyptic Theology,” “Christ, Spirit, and Salvation in an Apocalyptic Key,” and “Living Faithfully at the Turn of the Ages.” Ziegler states in the introduction to the book that “theology is required to think again about its own forms, methods, and foci precisely in virtue of its distinctly eschatological content.“1 Through three distinct movements in the book, he argues that Christian theology needs a paradigm shift that altogether accords with “the radicality, sovereignty, and militancy of adventitious divine grace.”2

Ziegler’s arguments are persuasive, and often while reading Militant Grace I found myself near to falling on my face in gratitude for the sheer inestimable magnitude of divine grace enacted for the rescue of sin-enslaved humanity (I may have done that once or twice). Thus my concerns, some of which are expressed below in the form of questions, do not constitute a dismissal of his work; rather, my potential disagreements should be read as vocalizations of praise for a work well composed.

In effect, Ziegler has issued a clarion call for the Church that holds great potential to rewrite not just theology but its necessary and attendant praxis, as we wait in the “spiritual insomnia”3 of prayer for the triumphant return of our Lord.

(I would like to note here my special thanks to Philip Ziegler for his warm welcome and willingness to answer the questions below, to Declan Kelly for facilitating my visit to Aberdeen, and to Louis McBride at Baker Academic for the review copy of Militant Grace.)

TB: Is not “militant” a loaded term to use in a Christian context? Shouldn’t we be wary of the horrible history of violent Christianity in the Crusades, the Holocaust et al?

PZ: Importantly, I think, the term is used here first and foremost as a predicate of God’s grace. It aims to emphasise the dynamic and polemical quality of God’s saving activity as reflected in the apocalyptic gospel. It serves as a shorthand reminder that to think and speak of grace evangelically is always to be concerned with an event of “the power of God for salvation” (Romans 1:16), namely, the invasive advent of divine salvation in Jesus Christ and its effective announcement in the Spirit’s power. As Donald MacKinnon once put it, the substance of the gospel is “God’s own protest against the world He has made, by which at the same time that world is renewed and reborn.” Grace ought not to be thought of apart from calling to mind God’s militancy to save his forlorn, rebellious and captive people, i.e., recalling the strident and relentless character of divine love that is the hallmark of God’s saving mission in the whole course of Christ’s obedience.

In the book’s final sentence I also characterise the Christian life as a “human life of faith now militant in love during the time that remains” (200). Importantly in this second use, the term modifies Christian love: again, “militant” here serves to stress the struggle that marks the life of faith, not least in the sustained experience of loving God and neighbours forthrightly. Following after the Crucified Nazarene—being drawn to where he himself is working in the power of the Spirit—cannot but involve struggle. This is not the struggle for salvation, to be sure, but rather the struggle to enact the gift of Christian freedom honestly and effectively in lives of service and witness in the midst of a world of virulent lovelessness.

TB: A keyword in apocalyptic theology is “disjuncture,” so that God’s act in Christ is seen as completely unprecedented, a “radical break with what has come before” (ch. 2). But, as Katherine Hockey so eloquently articulated at the symposium, what about what has come before? What of the prophecies of the prophets, the sacrificial typological system of the Israelite priesthood, even the promises to Abraham?

PZ: The positive claim at the heart of this is faith’s wondering confession of the sheer gratuity of God’s effective saving act in Jesus Christ. In him, saving divine grace comes upon a world in a way that overruns all “preparation” and “anticipation,” disrupting and often bypassing inherited and extant moral and religious forms. Grace “takes issue” here, we might say, with the complicity and ineffectualness of such traditions in the face of the captivity of sin. Christ comes into a world that has been, as Lou Martyn put it, “invaded by sin,” a religious and moral and political world captivated by the powers and principalities of “this passing age.” Importantly, “what has come before” has been subjected to sin’s distorting, corrupting, and enervating career. Paul’s acknowledgement—in the shadow of the cross—that the law cannot effect righteousness (Gal 2:1, 3:11, etc.), and all the more his agonizing puzzlement that for a world “sold under sin” the Law cannot but “bring death” (Rom 7:7-14), suggest that “all that had come before” had, in the matter of the salvation of those enslaved to Sin, come to naught.

PZ: The positive claim at the heart of this is faith’s wondering confession of the sheer gratuity of God’s effective saving act in Jesus Christ. In him, saving divine grace comes upon a world in a way that overruns all “preparation” and “anticipation,” disrupting and often bypassing inherited and extant moral and religious forms. Grace “takes issue” here, we might say, with the complicity and ineffectualness of such traditions in the face of the captivity of sin. Christ comes into a world that has been, as Lou Martyn put it, “invaded by sin,” a religious and moral and political world captivated by the powers and principalities of “this passing age.” Importantly, “what has come before” has been subjected to sin’s distorting, corrupting, and enervating career. Paul’s acknowledgement—in the shadow of the cross—that the law cannot effect righteousness (Gal 2:1, 3:11, etc.), and all the more his agonizing puzzlement that for a world “sold under sin” the Law cannot but “bring death” (Rom 7:7-14), suggest that “all that had come before” had, in the matter of the salvation of those enslaved to Sin, come to naught.

These claims are connected to Paul’s further witness to the depth of human plight, e.g., about God “handing over” sinners to their captor, Sin (Rom 1:24) and consigning “all in disobedience so that he may have mercy on all” (Rom 11:32). Note well – the reference here is not the promises, not the Torah, as such, but those inheritances inexplicably brought to naught in the world governed by “sin, death and the devil,” i.e., in the concrete situation of “the present age.” Perhaps we might say that the world into which the gospel erupts is already one markedly disjoined from “all that has come before” in virtue of the sway of sin. Saving divine grace disrupts and disjoins this already existing disjunction once more, as it were. The primary salutary disjunction in view is thus that between the Kingdom of God and the inimical and destructive pseudo-sovereignty of the “anti-god powers.” Within this—and only within this—there then arises and stands for Christian faith the important question of the relation between the divine salvation whose advent Christ is and the history of God’s way with his people Israel, between the new creation and the creation.

These claims are connected to Paul’s further witness to the depth of human plight, e.g., about God “handing over” sinners to their captor, Sin (Rom 1:24) and consigning “all in disobedience so that he may have mercy on all” (Rom 11:32). Note well – the reference here is not the promises, not the Torah, as such, but those inheritances inexplicably brought to naught in the world governed by “sin, death and the devil,” i.e., in the concrete situation of “the present age.” Perhaps we might say that the world into which the gospel erupts is already one markedly disjoined from “all that has come before” in virtue of the sway of sin. Saving divine grace disrupts and disjoins this already existing disjunction once more, as it were. The primary salutary disjunction in view is thus that between the Kingdom of God and the inimical and destructive pseudo-sovereignty of the “anti-god powers.” Within this—and only within this—there then arises and stands for Christian faith the important question of the relation between the divine salvation whose advent Christ is and the history of God’s way with his people Israel, between the new creation and the creation.

In the book, I am labouring chiefly to draw into sharp relief the scenario I’ve just described, and the discourse of “disjunction” aims to recover our sense of the primary breach that the advent of Christ’s saving lordship effects for those hitherto subjected to the sway of the “god(s) of this age.” Dr. Hockey was certainly right to espy that the discussion of the “second disjunction,” as it were, remains underdeveloped here: and it stands a critical task for any apocalyptic theology in this vein to address. Douglas Harink has, for example, directly addressed the specific question of the church, Israel and the spectre of supersessionism in relation to Paul’s apocalyptic gospel in several essays I would recommend, including “Paul and Israel: An Apocalyptic Reading” (Pro Ecclesia 16:4, pp. 359ff.) and “Barth’s Apocalyptic Exegesis and the Question of Israel in Römerbrief, Chapters 9-11” (Toronto Journal of Theology 25:1, pp. 5ff.).

One theological consideration is to acknowledge that it is the nature of the ever new thing God does in Christ to render old and past primarily everything that stands in enmity towards it. This means that not only what has chronologically preceded it, but also everything which comes after it and which continues absurdly in contradiction to it, is overreached, set aside and destined to pass away. This ever new thing does, of course, connect itself graciously with the chronological past just as it does with the chronological future. The continuity in any case is on God’s side—God’s way with the wayward world is one of intractable, indeed militant, faithfulness. That this takes the form or comes upon creatures as serial, and radical disruption might also be taken to be that the very witness of Israel’s prophets.

TB: How would you define the term “apocalyptic,” and is there a better term that perhaps describes more precisely your own stream of apocalyptic theology?

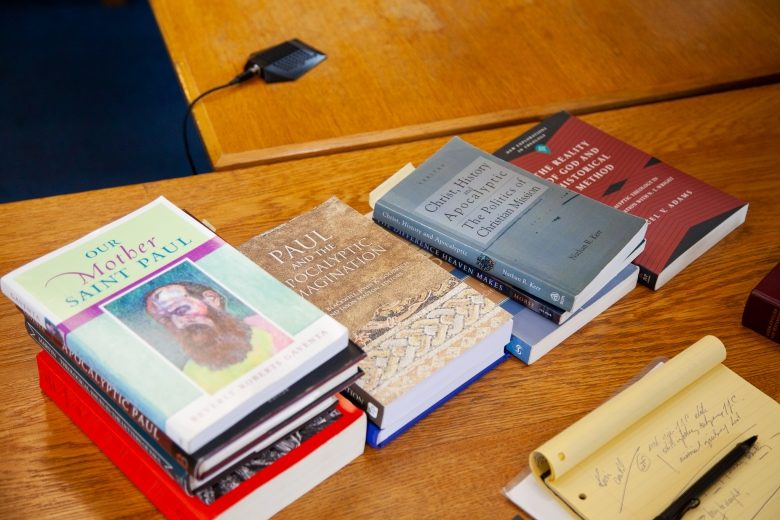

PZ: I certainly do not have a monopoly on the term “apocalyptic” of course, and it is scarcely self-evident as to what it ought to be taken to mean! The word enjoys wide and contested use, both scholarly and popular, and there are a good many “apocalyptic” sensibilities and theological concepts that differ notably from what I have in view. My hope is that the specific theological meaning of “apocalyptic” I want to recommend and with which I work here is built up and demonstrated by its use across the whole of the book. I do venture some specific clarifications in the early pages of the book that readers might find helpful. First, the project is in the first instance indexed to a reading of Paul, and so the concept of apocalyptic finds its primary reference points there. My usage thus draws upon those Pauline scholars with whom I am in close dialogue, e.g., Käsemann, Martyn, de Boer, Gaventa, Campbell, and others. Beverly Gaventa winsomely characterises the matter this way:

PZ: I certainly do not have a monopoly on the term “apocalyptic” of course, and it is scarcely self-evident as to what it ought to be taken to mean! The word enjoys wide and contested use, both scholarly and popular, and there are a good many “apocalyptic” sensibilities and theological concepts that differ notably from what I have in view. My hope is that the specific theological meaning of “apocalyptic” I want to recommend and with which I work here is built up and demonstrated by its use across the whole of the book. I do venture some specific clarifications in the early pages of the book that readers might find helpful. First, the project is in the first instance indexed to a reading of Paul, and so the concept of apocalyptic finds its primary reference points there. My usage thus draws upon those Pauline scholars with whom I am in close dialogue, e.g., Käsemann, Martyn, de Boer, Gaventa, Campbell, and others. Beverly Gaventa winsomely characterises the matter this way:

“Paul’s apocalyptic theology has to do with the conviction that in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, God has invaded the world as it is, thereby revealing the world’s utter distortion and foolishness, reclaiming the world, and inaugurating a battle that will doubtless culminate in the triumph of God over all God’s enemies (including the captors Sin and Death). This means that the Gospel is first, last, and always about God’s powerful and gracious initiative.” (Our Mother Saint Paul, p. 81)

“Paul’s apocalyptic theology has to do with the conviction that in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, God has invaded the world as it is, thereby revealing the world’s utter distortion and foolishness, reclaiming the world, and inaugurating a battle that will doubtless culminate in the triumph of God over all God’s enemies (including the captors Sin and Death). This means that the Gospel is first, last, and always about God’s powerful and gracious initiative.” (Our Mother Saint Paul, p. 81)

To this I might add that apocalyptic, for me, denotes the distinctive form of God’s eschatological activity to which the Gospel attests, that new and unrivalled thing God does in Jesus Christ to redeem, rescue, rectify and so to save. The ideas of salvation as a “three agent drama,” of the cosmic scope of this drama, of the event of Jesus Christ as the “turning of the ages,” and of the radicality of the epistemic and ethical revolution thus inaugurated—these are all key elements of the Pauline apocalyptic on which I am drawing. In the opening essay to the edited volume, Paul and the Apocalyptic Imagination, Blackwell, Goodrich and Maston refer to this view of apocalyptic as “eschatological invasion.” The six programmatic theses that conclude the second chapter (pp. 36-31) also suggest something of the central meaning of the term “apocalyptic” when used to characterise the particular theological posture I am wanting to occupy. I’m after a term that, tracking closely with the features of Paul’s gospel witness in the first instance, helps me to bespeak the radicality and dynamism of divine grace.

TB: One particular phrase that you used a few times in response to questions during the symposium was that “Grace is catastrophic.” Can you unpack that a bit for us? Isn’t grace just this benevolent force for good, God’s love-gift for humanity that helps us have better marriages, better job prospects, and just a more abundant life overall?

PZ: God’s grace is catastrophic precisely because it is divine saving grace. Given our captivity in sin—and, crucially, the manifold forms in which we are absurdly and self-destructively complicit with our captivity—salvation entails the bringing to an end of all this for the sake of the gift and advent of something new. In an ancient Greek drama, a καταστροφή was a surprising turn of events that brought the plot of a play to a surprising conclusion, and more generally the term denotes an unanticipated event that serves to subvert the order of things, to “throw things over” as the etymology suggests. When I use the word of God’s grace I’m drawing on these primary meanings. The advent of grace ends our world of sin, and only thus begins the new world of faith. Because we are integrated fully into our world—as Käsemann says, we are but portions of it—everything must be lost in order for everything to be gained. In coming for us, God’s grace comes against us in the first instance, to shake us loose or knock us sideways to the world of sin in which we’ve settled.

The New Testament language of “dying with Christ” expresses this sharply (e.g., 2 Cor 5:15-17) as does Paul’s extraordinary confession that in virtue of the gracious saving work of God in Christ he has been “crucified to the world” and the “world crucified to him” (Gal 6:14) such that that which used to provide orientation—circumcision, the Law, etc.—no longer does so. He has suffered a disaster at the hands of divine grace: i.e., he has lost the whole course of “stars” by which he once was able to navigate life (dis-astra) because the order of things has been toppled by the gracious advent of the new creation (Gal 6:16). To say that grace is catastrophic is to try to draw attention to all this as a fundamental and inalienable feature of the gospel and so also of our thinking and living in its wake. The essays in the volume that explore questions of moral law and the Christian life are attempts to gesture at the sorts of difference such an acknowledgment might make.

The New Testament language of “dying with Christ” expresses this sharply (e.g., 2 Cor 5:15-17) as does Paul’s extraordinary confession that in virtue of the gracious saving work of God in Christ he has been “crucified to the world” and the “world crucified to him” (Gal 6:14) such that that which used to provide orientation—circumcision, the Law, etc.—no longer does so. He has suffered a disaster at the hands of divine grace: i.e., he has lost the whole course of “stars” by which he once was able to navigate life (dis-astra) because the order of things has been toppled by the gracious advent of the new creation (Gal 6:16). To say that grace is catastrophic is to try to draw attention to all this as a fundamental and inalienable feature of the gospel and so also of our thinking and living in its wake. The essays in the volume that explore questions of moral law and the Christian life are attempts to gesture at the sorts of difference such an acknowledgment might make.

TB: What is the place of human agency, as you see it, in apocalyptic theology? In other words, is there any place for human will, the right to choose God over the Devil, in a theological outlook that sees God as a militant being who captures his own enemies and transforms them, by his power, into his own children (see ch. 4)? If this is the case, what hope does any individual human being have?

PZ: No, there is not any such place. God’s saving grace finds us in sin, already in the posture of “polemical untruth” as Kierkegaard aptly described it. The actual situation is, as Paul says, that “while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us . . . while were God’s enemies, we were reconciled to God by the death of his Son” (Rom 5:8-10). The truth of the doctrine of original sin is that when grace finds us we find ourselves to have already been in sin and enmity against God.

PZ: No, there is not any such place. God’s saving grace finds us in sin, already in the posture of “polemical untruth” as Kierkegaard aptly described it. The actual situation is, as Paul says, that “while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us . . . while were God’s enemies, we were reconciled to God by the death of his Son” (Rom 5:8-10). The truth of the doctrine of original sin is that when grace finds us we find ourselves to have already been in sin and enmity against God.

Faith is “a busy and active thing” as Luther said. And discipleship is nothing if not our active service and witness to the God of the gospel in the power of the Spirit. God’s saving action frees, disposes, orients and empowers us for that decidedly human action which is given to us to undertake, of which grateful praise, service, and witness are the cardinal forms. So theology has much to say of human willing and doing to be sure. But none of this authorises or admits the idea of a neutral place or posture from which we might adjudicate coolly and by right between aligning ourselves with the love of God and serving all that is arrayed against it. Of course, to assume such a posture would—if it were possible—already be a polemical action in contradiction to the truth; it would be unbelief, it would be sin.

Surely all our hope—just as our faith—is suspended from the only thing it could ever be, namely God’s sovereign mercy for us in Jesus Christ.

TB: Apocalyptic theology has sometimes been accused of universalism, leaving open the question of what happens to non-Christians at the eschaton. Chapter 7 of Militant Grace lays out a picture of final judgment as an act of love, without the mention of wrath: “God’s way of judgment is a path of which the truth of our lives is illumined and decided by the only One competent to do so; it is a path on which everything we are that is born of death is repudiated in love and set aside forever”. Does apocalyptic theology, as you see it, border on universalism, or is it so intently focussed on the Christian experience that the question of judgment for unbelievers is laid aside?

PZ: The thesis of that chapter of the book is that divine judgment simply is that final act of militant grace in which in the course of the outworking of God’s sovereign mercy, “everything we are that is born of death is repudiated in love and set aside forever.” I take that claim to be a universal one: it is a truth Christian faith confesses concerning all of humanity as such. To speak of divine wrath in this context would be to speak precisely of the total and final repudiation by the love of God of all that is inimical to it; wrath would bespeak the eschatological consumption of the whole loveless history of creaturely faithlessness and its consequences in the fire of God’s holy love. Just as there is no room in this apocalyptic theology for the notion of a neutral human will at liberty by rights to choose between God and Sin, so too here it becomes impossible to conceive of belief as a virtuous human work that decides our destiny.

PZ: The thesis of that chapter of the book is that divine judgment simply is that final act of militant grace in which in the course of the outworking of God’s sovereign mercy, “everything we are that is born of death is repudiated in love and set aside forever.” I take that claim to be a universal one: it is a truth Christian faith confesses concerning all of humanity as such. To speak of divine wrath in this context would be to speak precisely of the total and final repudiation by the love of God of all that is inimical to it; wrath would bespeak the eschatological consumption of the whole loveless history of creaturely faithlessness and its consequences in the fire of God’s holy love. Just as there is no room in this apocalyptic theology for the notion of a neutral human will at liberty by rights to choose between God and Sin, so too here it becomes impossible to conceive of belief as a virtuous human work that decides our destiny.

Again, the gospel tells precisely of a God who lovingly delivers his beloved creatures into a destiny they could not, would not, and do not choose for themselves in their sin. I take the proximate concern of the doctrine of the Last Judgment to be the animation and direction of the specifically Christian life, and so to the extent that one is concerned with the fate of unbelief, one is rightly driven to reflection and repentance oneself. It is my unbelief—our unbelief—and everything to which it gives rise that stands under the promise of God’s final loving repudiation. That God saves us in spite of our unbelief is the ground of Christian hope.

Philip Ziegler’s Militant Grace: The Apocalyptic Turn and the Future of Christian Theology (Baker Academic, 2018) is now available on pre-order for the Logos Digital Library at the special pre-production price of $21.99.

Philip Ziegler’s Militant Grace: The Apocalyptic Turn and the Future of Christian Theology (Baker Academic, 2018) is now available on pre-order for the Logos Digital Library at the special pre-production price of $21.99.

[…] https://academic.logos.com/militant-grace-an-interview-and-photo-essay-with-philip-ziegler/ […]

[…] via Militant Grace: an Interview and Photo Essay with Philip Ziegler — theLAB […]

[…] https://academic.logos.com/militant-grace-an-interview-and-photo-essay-with-philip-ziegler/ […]

[…] https://academic.logos.com/militant-grace-an-interview-and-photo-essay-with-philip-ziegler/ […]

[…] Tavis Bohlinger’s photo essay and interview from the Aberdeen postgraduate symposium on the book in June 2018. […]