February 8 marks International Septuagint day, a day to celebrate the Septuagint and encourage its study. This date was established in 2006 because Robert Kraft observed that it is the only one we have record of being historically related to the Greek Scriptures.

In a document dating to February 8, 533 CE, the Emperor Justinian grants his permission for the public reading of Jewish Scriptures in the Roman Empire in any language.

But where Greek is used he states that “those who use Greek shall use the text of the seventy interpreters, which is the most accurate translation, and the one most highly approved…” The text he refers to is, of course, the Septuagint.

In honour of Septuagint Day, I am eager to discuss ancient manuscripts of the LXX, in particular those manuscripts that have recently been made accessible to the public by the Vatican Library Digitization Project. This project greatly improves our access to ancient treasures that further our understanding of the Bible and its history.

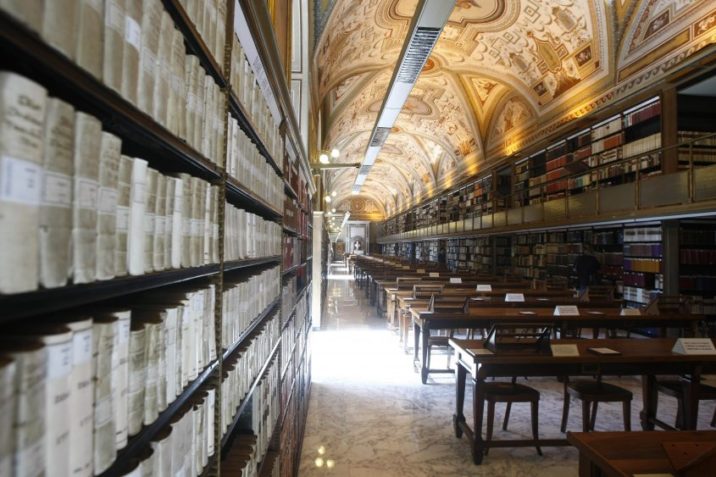

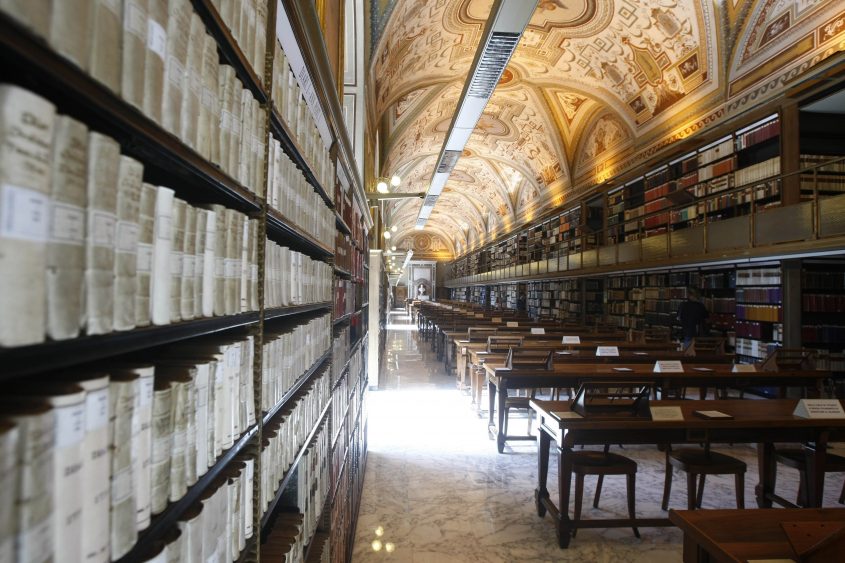

The Vatican Apostolic Library

The Vatican Apostolic Library (Bibliotheca apostolica vaticana) contains a collection of manuscripts, incunabula (books printed before 1500), and printed books. The initiative to establish a public library was undertaken by pope Pope Nicholas V in the early 1450s.

Popes had always collected books for their own private libraries. In the Middle Ages, important collections of books were mostly confined to churches, monasteries, and wealthy individuals.

Pope Nicholas V (1447–1455), a humanist at heart who wanted to revive Rome, envisioned a public library for scholarly use, and so a Library as a distinct entity, with funds devoted to its existence, came into being in 1450. The collection is said to have consisted of 1,200 entries.

Nicholas’s death kept him from completing his dream, but the idea of a public library was taken up by pope Sixtus IV (1471–1484), who acquired many books and established a permanent area inside the Vatican palace to house the collections.

In 1475, the library prepared the first catalogue of its holdings. Over the next 600 years, the Vatican’s collection increased exponentially. To date, the Vatican Library houses approximately 80,000 manuscripts, 8,000 incunabula, and almost 2 million printed books.

Even though the collection of printed books is not large in number (the largest libraries in the world hold well over 30 million books), the percentage of rare and valuable works is much greater than is found in any other library of such proportions.

While the Vatican Library has always included Bibles, canon law texts and theological works, it specialized in secular books from the beginning. Its collection of Greek and Latin classics was at the center of the revival of classical culture during the Renaissance age.

The Vatican Digitization Project

Access to the Library nowadays is restricted. Fortunately, in 2010, the Vatican Library set up a large-scale project to digitize the entire collection and make it accessible to the public. On their website (see below), you can browse through photographs (albeit of varying quality) of manuscripts and incunabula for literally hours (even days!).

To date, over 13,000 manuscripts have been digitized. Among them are many important textual witnesses to the Septuagint. These photographs enable us not only to consult the Greek biblical texts for ourselves rather than relying on modern editions, but also to read and to interpret the marginal notes.

Looking at the real thing

Of course, one of the most well-known manuscripts of the Septuagint is the Codex Vaticanus. This manuscript was part of the library’s founding collection in 1450.

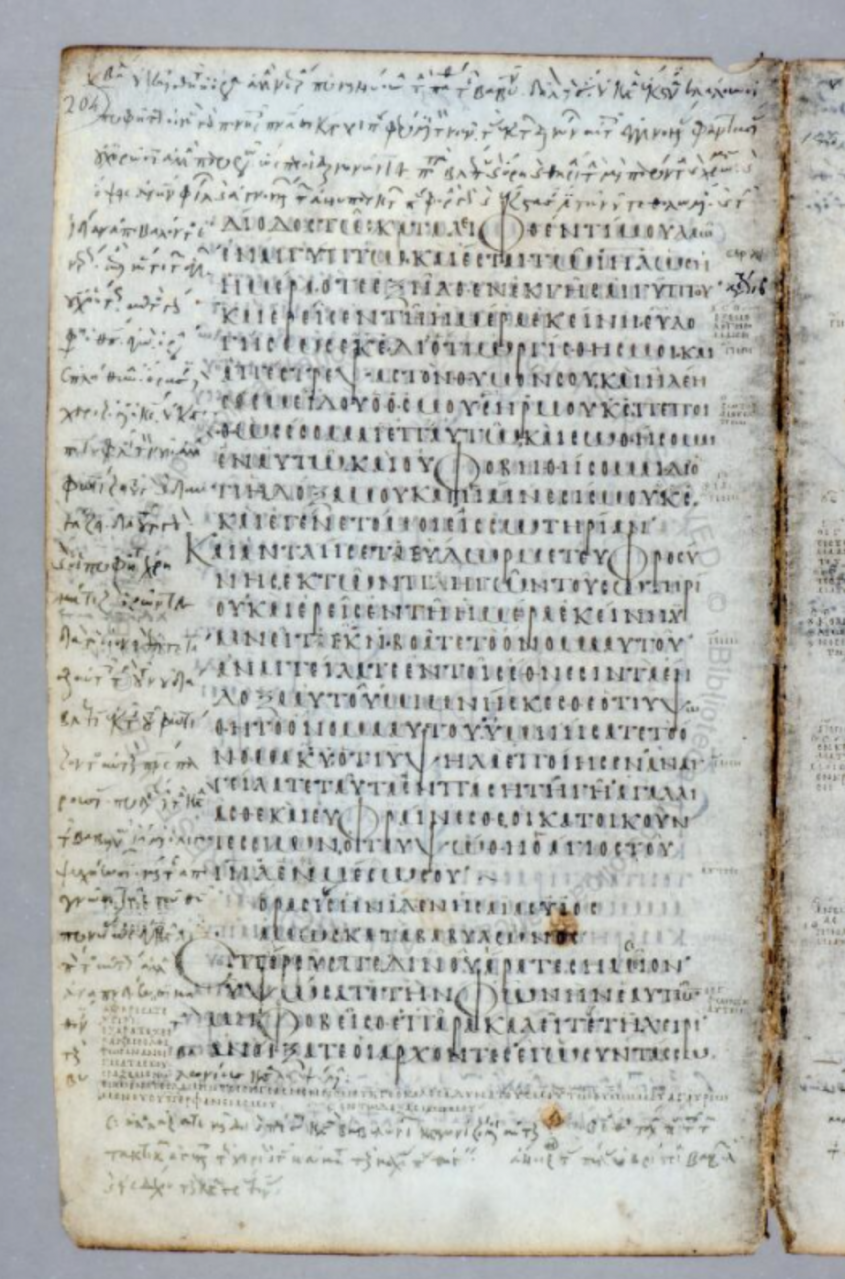

Let’s briefly take a closer look at two recently uploaded manuscripts in more detail. The first one is Codex Marchalianus (Vat.gr. 2125), also referred to by its siglum Q.

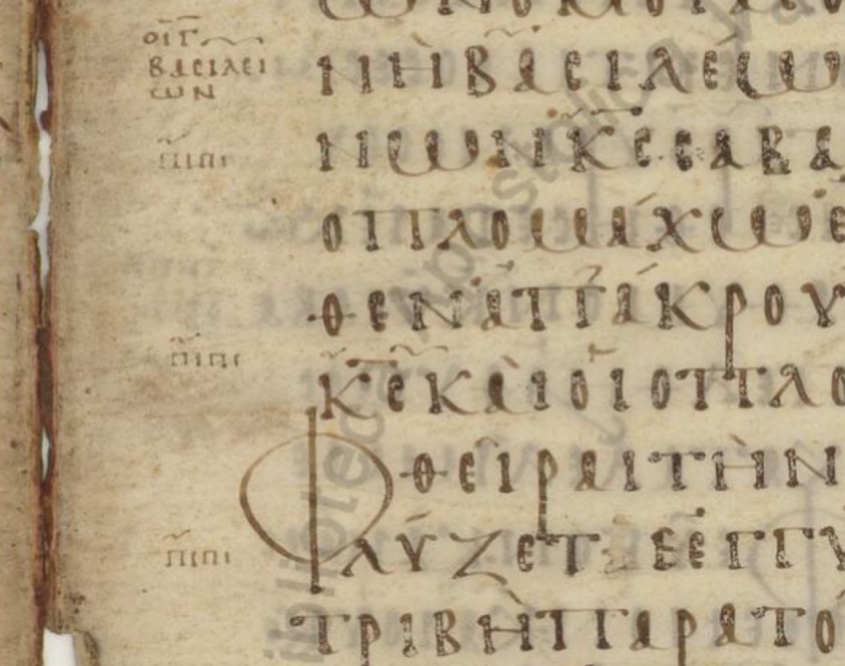

Q is dated to the sixth century. The text is written on vellum in uncial letters. This manuscript contains the Twelve Prophets, the Book of Isaiah, the Book of Jeremiah (with Baruch, Lamentations, and the Epistle), the Book of Ezekiel, and the Book of Daniel (the Theodotion version, with Susanna and Bel).

The manuscript includes about seventy items of an onomasticon of proper names in the margins of the texts of Ezekiel and Lamentations, as well as hexaplaric readings, as you can see in this picture of slide 204 of the manuscript, containing the text of Isaiah 11:16-13:2:

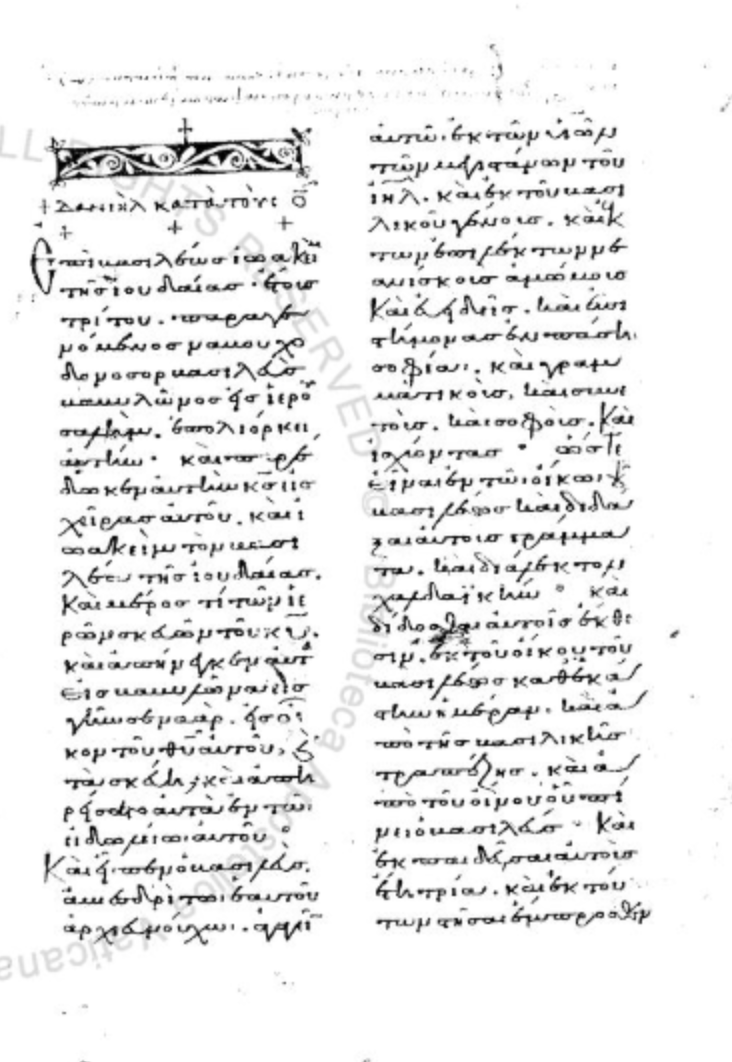

The Codex Marchalianus is important in the debate about the use of the tetragrammaton. At times, the marginal notes in Q attest to the use of the Greek transliteration ΙΑΩ for the Divine Name or the transcription of the tetragrammaton in Greek letters, ΠΙΠΙ.

In this picture of slide 205 of the manuscript, for example, we encounter the Greek tetragrammaton repeatedly in the left margin:

The second example, Chig.R.VII. 45, is known as Codex Chisianus 45 or Manuscript 88 according to Rahlfs’s catalogue of Septuagint manuscripts.

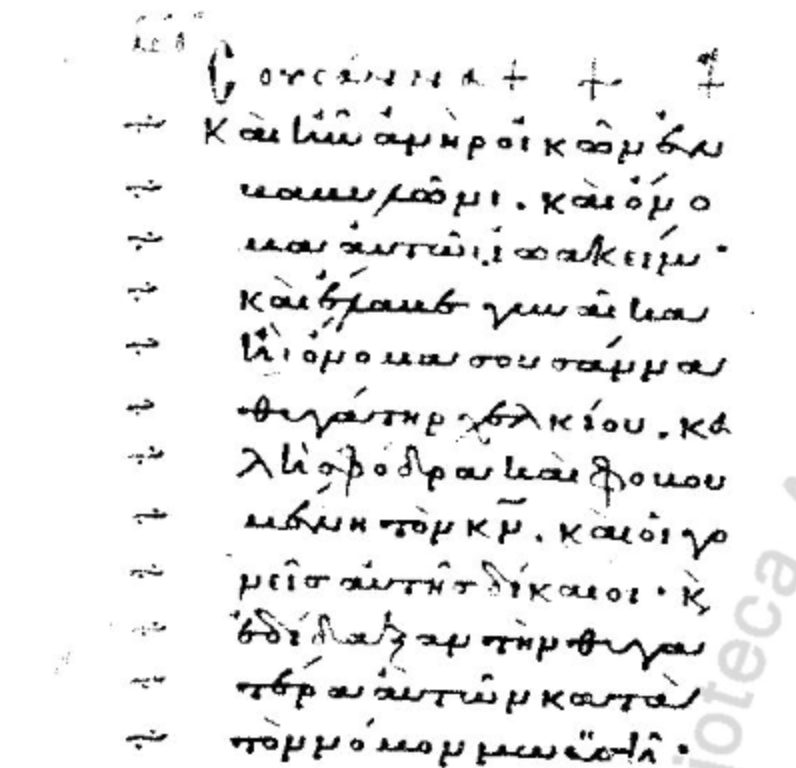

Mss 88 is a tenth century manuscript, written in minuscules on parchment. It purports to be directly derived from the recension of the Septuagint made by Origen in the third century CE. It contains Jeremia (including Baruch, Lamentations, and the Epistle), Daniel (the Theodotion version, including Susanna and Bel, and with comments by Hippolytus of Rome) as well as Daniel in the Old Greek, Ezekiel, and Isaiah.

Particularly interesting about this manuscript is that it includes both versions of the book of Daniel. The (earlier) Old Greek translation, of which few witnesses remain, had been supplanted by the Theodotion version by the first or second century CE.

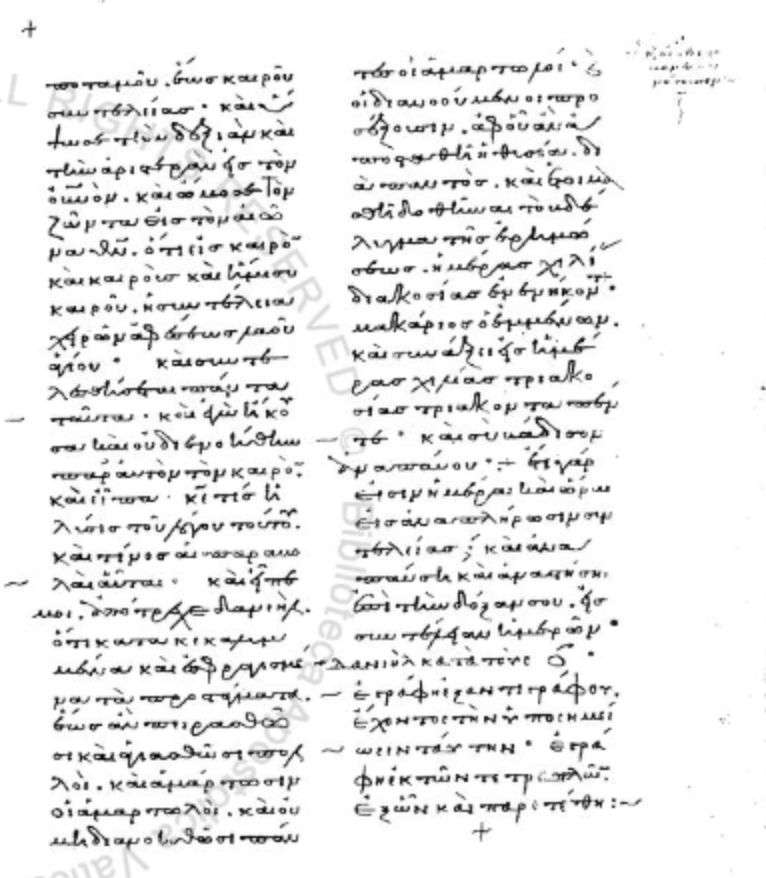

Ms 88 was the only surviving version of Old Greek Daniel until the 1931 discovery of Papyrus 967. The Old Greek text starts on slide 148:

You can also see the tetraplaric colophon after Dan 12 on slide 180, with Susanna beginning just after on slide 181 with the first five verses obelized:

Therefore, in honour of the eleventh International Septuagint Day, I propose that we put our editions aside and read actual Greek manuscripts!

Notes:

- All manuscript pictures are copyright of the Vatican Library.

- I wish to thank Bradley Marsh for alerting me when new manuscripts appear online.

- For an exceptional research tool with access to over 87 LXX manuscripts (and growing), see the interactive Septuagint Manuscript Explorer, available on all higher Logos 7 base packages.